Part 2. Distributed Data

Chapter 7. Transactions

Transaction is the way for an application to group several reads and writes together into a logical unit.

Conceptually, all reads and writes are executed as one operation: either transaction succeds (commit) or fails (rollback).

- When fails can be retried

- Error handling is much simpler

Transactions are not the law of nature, they were created with a purpose to simplify the programming model for applications to accessing the database. By using transactions, it's free to ignore some potential problems, because database takes care them instead (safety guarantees).

You need to understand where to use transactions and where not to use them.

The Slippery Concept of a Transaction

NoSQL hype which aimed to improve scalability and performance, by abandoning transactions.

The truth is not that simple: like every other technical design choice, transactions have advantages and limitations.

The Meaning of ACID

Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability

Systems which not meet the ACID criteria sometimes called BASE (Basically Available, Soft state, Eventual consistency).

Atomicity

In general, atomic refers to something that cannot be broken down into smaller parts.

The word means simular but subtly different things in different branches of computing.

In multi-threaded programming, if one thread executes an atomic operation, that means there is no way to another thread could see the operation only partially completed.

In the context of ACID, atomicity is not about concurrency. It doesn't describe what happens if several processes try to access the same data at the same time - is covered by isolation.

Atomicity describes what happens if a client wants to make several writes, but a fault occurs after some of the writes have been processed.

If writes are grouped together into an atomic transaction and she can't be completed, then the transaction is aborted and the database must discard or undo any writes it has made so far in that transaction.

Without atomicity, if an error occurs partway through making multiple changes, it’s difficult to know which changes have taken effect and which haven’t.

Perhaps abortability would have been a better term than atomicity, but we will stick with atomicity since that’s the usual word.

Consistency

This word is terribly overloaded.

- Replica consistency and the issue of eventual consistency that arises in async replicated systems.

- Consist hashing is an approach to partitioning that some systems use for rebalancing.

- In CAP theorem, consistency means linearizability.

- In ACID, consistency refers to an application-specific notion of the database being in a “good state”.

If you have certain statements about your data (invariants) that must always be true.

The database should always change from one valid state to another valid state.

Consistency is a property of the application, when AID is a property of the database.

The letter C doesn't really belong in ACID.

Isolation

Most databases are accessed by several clients at the same time. That is no problem if they are reading and writing different parts of the database, but if they are accessing the same database records, you can run into concurrency problems (race conditions).

Isolation in the sense of ACID means that concurrently executing transactions are isolated from each other: they cannot step on each other’s toes.

Isolation often formalized as a serilizability, which means that each transaction can pretend that it is the only transaction running on the entire database.

The database ensures that when the transactions have committed, the result is the same as if they had run serially (one after another), even though in reality they may have run concurrently.

Durability

The purpose of a database system is to provide a safe place where data can be stored without fear of losing it.

Durability is the promise that once a transaction has com‐ mitted successfully, any data it has written will not be forgotten, even if there is a hardware fault or the database crashes.

In a single-node database, durability typically means that the data has been written to nonvolatile storage such as a hard drive or SSD.

In a replicated database, durabil‐ ity may mean that the data has been successfully copied to some number of nodes. In order to provide a durability guarantee, a database must wait until these writes or replications are complete before reporting a transaction as successfully committed.

Perfect durability doesn't exist: if all your hard disks and all your backups are destroyed at the same time.

Single-Object and Multi-Object Operations

Recap in ACID:

- Atomicity

all-or-nothing guarantee

- Isolation

transactions can run concurrently without messing each other up

Multi-object transactions are often needed if several pieces of data need to be kept in sync.

- Violating isolation: one transaction reads another transaction's uncommitted writes (dirty read)

Multi-object transactions require some way of determining which read and write operations belong to the same transaction. In relational databases, that is typically done based on the client’s TCP connection to the database server: on any particular connection, everything between a BEGIN TRANSACTION and a COMMIT statement is considered to be part of the same transaction.

On the other hand, many NoSQL databases don't have such a way of grouping operations together.

Single-object writes

Atomicity and isolation are also apply when single object is being changed.

e.g writing a 20 Kb json document to a database, that may failure halfway through writing.

Atomicity can be implemented by using a log for crash recovery, and isolation can be implemented by using a lock on each object (allowing only one transaction to access the object at a time).

Some databases also provide more complex atomic operations, such as incrementing operation, which removes the need for a read-modify-write cycle.

Simularly popular is a compare-and-set operation, which allows a write to happen only if the value has not been concurrently changed by someone else.

These single-object operations are useful, as they can prevent lost updates when sev‐ eral clients try to write to the same object concurrently.

However, they are not transactions in the usual sense of the word. Compare-and-set and other single-object operations have been dubbed “light‐ weight transactions”.

A transaction is usually understood as a mechanism for grouping multiple operations on multiple objects into one unit of execution.

The need for multi-object transactions

Not implemented in multiple databases, because it's hard to implement it across partitions and in some cases high availability or performance is more important.

There are some use cases in which single-object inserts, updates, and deletes are sufficient:

- Row of one table have a reference to a row in another table.

Multi-object transactions allow you to ensure that these refer‐ ences remain valid: when inserting several records that refer to one another, the foreign keys have to be correct and up to date, or the data becomes nonsensical.

Updating a denormalized information (update several objects in one go)

Maintaining indexes

Update of column triggers an update of secondary index.

Such applications can still be implemented without transactions. However, error han‐ dling becomes much more complicated without atomicity, and the lack of isolation can cause concurrency problems.

Handling errors and aborts

A key feature - abort of a transaction.

Not all systems follow that phlosophy, e.g datastores with leaderless replication work much more on a "best effort" basis - "database will do much as it can, and if it runs into an error, it won't undo something it has already done". So that's an application responsibility to recover from errors.

Errors will inevitably happen, but many software developers prefer to think only about the happy path rather than the intricacies of error handling.

Retrying an aborted transaction is a simple and effective error handling mechanism, it isn’t perfect:

If the transaction actually succeeded, but the network failed while the server tried to acknowledge the successful commit to the client (so the client thinks it failed), then retrying the transaction causes it to be performed twice—unless you have an additional application-level deduplication mechanism in place.

If the error is due to overload, retrying the transaction will make the problem worse, not better. To avoid such feedback cycles, you can limit the number of retries, use exponential backoff, and handle overload-related errors differently from other errors (if possible).

It is only worth retrying after transient errors (for example due to deadlock, isolation violation); after a permanent error (such as constraint violation) a retry will simply fail again.

If the transaction also has side effects outside of the database, those side effects may happen even if the transaction is aborted.

If the client process fails while retrying, any data it was trying to write to the database is lost.

Weak Isolation Levels

If two transactions don't touch the same data, they can safety execute in parallel.

Concurrency is hard and databases a trying to hide concurrency issues from application developers by providing transaction isolation.

Serializable isolation means that the databases guarantees that transactions have the same effect as if the run serially (one after another) without any concurrency.

In practice, isolation is unfortunately not that simple. Serializable isolation has a performance cost, and many databases don’t want to pay that price.

Read Committed

- No dirty reads

When reading you will only see data that has been committed.

- No dirty writes

When writing you will only overwrite data that has been committed.

No dirty reads

Can another transation see data of another transaction that has not been committed yet? If yes, then it's called dirty read.

When to prevent dirty reads?

- If a transaction needs to update several objects

- If a transaction aborts, any writes it has made need to be rolled back

No dirty writes

What happens if two transactions concurrently try to update the same object in a database? We don’t know in which order the writes will happen, but we normally assume that the later write overwrites the earlier write.

By preventing dirty writes, this isolation level avoids some kinds of concurrency problems:

If transactions update multiple objects, dirty writes can lead to a bad outcome.

However, read committed does not prevent the race condition between two counter increments

Implementing read committed

Most commonly, databases prevent dirty writes by using row-level locks: when a transaction wants to modify a particular object (row or document), it must first acquire a lock on that object.

How do we prevent dirty reads? One option would be to use the same lock, and to require any transaction that wants to read an object to briefly acquire the lock and then release it again immediately after reading.

However, the approach of requiring read locks does not work well in practice, because one long-running write transaction can force many read-only transactions to wait until the long-running transaction has completed.

Better solution: for every object that is written, the database remembers both the old com‐ mitted value and the new value set by the transaction that currently holds the write lock.

Snapshot Isolation and Repeatable Read

Nonrepeatable read or read skew is when a transaction reads the same item several times and sees different results each time.

Read skew is considered acceptable under read committed isolation.

However, some situations cannot tolerate such temporary inconsistency:

- Backups

Taking a backup requires making a copy of the entire database, which may take hours on a large database. During the time that the backup process is running, writes will continue to be made to the database.

- Analytic queries and integrity checks

Sometimes, you may want to run a query that scans over large parts of the database.

Snapshot isolation is the most common solution to this problem.

The idea is that each transaction reads from a consistent snapshot of the database—that is, the trans‐ action sees all the data that was committed in the database at the start of the transaction.

Even if the data is subsequently changed by another transaction, each transaction sees only the old data from that particular point in time.

Implementing snapshot isolation

Like read committed isolation, implementations of snapshot isolation typically use write locks to prevent dirty writes.

However, reads do not require any locks. From a performance point of view, a key principle of snapshot isolation is readers never block writers, and writers never block readers.

This allows a database to handle long-running read queries on a consistent snapshot at the same time as processing writes normally, without any lock contention between the two.

The database must potentially keep several different committed versions of an object, because various in-progress trans‐ actions may need to see the state of the database at different points in time. Because it maintains several versions of an object side by side, this technique is known as multiversion concurrency control (MVCC).

However, storage engines that support snapshot isolation typically use MVCC for their read committed isolation level as well. A typical approach is that read committed uses a separate snapshot for each query, while snapshot isolation uses the same snapshot for an entire transaction.

Visibility rules for observing a consistent snapshot

When a transaction reads from the database, transaction IDs are used to decide which objects it can see and which are invisible.

At the start of each transaction, , the database makes a list of all the other transactions that are in progress. Any writes that those transactions have made are ignored.

Any writes made by aborted transactions are ignored.

Any writes made by transactions with a later transaction ID

All other writes are visible to the application’s queries.

These rules apply to both creation and deletion of objects.

Indexes and snapshot isolation

How do indexes work in a multi-version database? One option is to have the index simply point to all versions of an object and require an index query to filter out any object versions that are not visible to the current transaction.

In practice, many implementation details determine the performance of multi-version concurrency control.

Postgres avoiding indexes update if different versions of the same object can fit on the same page.

Another approach is to use append-only/copy-on-write B-tree indexes, which not overwrite pages of the tree when they are updated, but instead creates a new copy of the page with the updated data.

Parent pages, up to the root of the tree, are copied and updated to point to the new versions of their child pages. Any pages that are not affected by a write do not need to be copied, and remain immutable.

With append-only B-trees, every write transaction (or batch of transactions) creates a new B-tree root, and a particular root is a consistent snapshot of the database at the point in time when it was created. There is no need to filter out objects based on transaction IDs because subsequent writes cannot modify an existing B-tree.

It also requires a garbage-collection process to clean up old B-tree roots that are no longer needed.

Repeatable read and naming confusion

Several databases implement repeatable read, there are big differ‐ ences in the guarantees they actually provide, despite being ostensibly standardized.

As a result, nobody really knows what repeatable read means.

Preventing Lost Updates

The read committed and snapshot isolation levels we’ve discussed so far have been primarily about the guarantees of what a read-only transaction can see in the pres‐ ence of concurrent writes.

We have mostly ignored the issue of two transactions writing concurrently - we have only discussed dirty writes.

Lost update can occur if an application reads some value from the database, modifies it, and writes back the modified value. If two transactions do it concurrently, one of the modifications can be lost, because the second doesn't include info about first modification.

Some scenarios:

- Incrementing a counter or updating (reading, calculating, writing back)

- Editing the same document by two users concurrently

Atomic write operations

Many databases provide atomic update operations, which remove the need to imple‐ ment read-modify-write cycles in application code.

UPDATE counters SET value = value + 1 WHERE key = 'foo';UPDATE counters SET value = value + 1 WHERE key = 'foo';This query is concurrent-safe in most databases.

Atomic operations are usually implemented by taking an exclusive lock on the object when it is read.

Another option is to simply force all atomic operations to be executed on a single thread.

Explicit locking

Another option for preventing lost updates, if the database’s built-in atomic opera‐ tions don’t provide the necessary functionality, is for the application to explicitly lock objects that are going to be updated.

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

SELECT * FROM figures

WHERE name = 'robot' AND game_id = 222 FOR UPDATE;

-- Check whether move is valid, then update the position -- of the piece that was returned by the previous SELECT. UPDATE figures SET position = 'c4' WHERE id = 1234;

COMMIT;BEGIN TRANSACTION;

SELECT * FROM figures

WHERE name = 'robot' AND game_id = 222 FOR UPDATE;

-- Check whether move is valid, then update the position -- of the piece that was returned by the previous SELECT. UPDATE figures SET position = 'c4' WHERE id = 1234;

COMMIT;The

FOR UPDATEclause indicates that the database should take a lock on all rows returned by this query.

This works, but to get it right, you need to carefully think about your application logic. It’s easy to forget to add a necessary lock somewhere in the code, and thus introduce a race condition.

Automatically detecting lost updates

An alternative is to allow them to execute in parallel and, if the transaction manager detects a lost update, abort the transaction and force it to retry its read-modify-write cycle.

An advantage of this approach is that databases can perform this check efficiently in conjunction with snapshot isolation.

Lost update detection is a great feature, because it doesn’t require application code to use any special database features.

Compare-and-set

The purpose of this operation is to avoid lost updates by allowing an update to happen only if the value has not changed since you last read it.

-- This may or may not be safe, depending on the database implementation

UPDATE wiki_pages SET content = 'new content'

WHERE id = 1234 AND content = 'old content';-- This may or may not be safe, depending on the database implementation

UPDATE wiki_pages SET content = 'new content'

WHERE id = 1234 AND content = 'old content';However, if the database allows the WHERE clause to read from an old snapshot, this statement may not prevent lost updates, because the condition may be true even though another concurrent write is occurring.

Conflict resolution and replication

Locks and compare-and-set operations assume that there is a single up-to-date copy of the data. However, databases with multi-leader or leaderless replication usually allow several writes to happen concurrently and replicate them asynchronously.

Common approach in such replicated databases is to allow concurrent writes to create several conflicting versions of a value (also known as siblings), and to use application code or special data structures to resolve and merge these versions after the fact.

Write Skew and Phantoms

With dirty writes and lost updates may occurs write skew.

Characterizing write skew

You can think about write skew as a generalization of the lost update problem. Write skew can occur when two transations read the same object, and them updates some of those objects (different transactions may update different objects). In special cases where different transactions update the same object, you get a dirty write or lost update anomaly.

Opportunity to make an update for some true statement, that will return false if operations are done in subsequent way.

Options for fixing the write skew:

Atomic single-object operations don't help, as multiple objects are involved.

Automatic detection of lost updates, which can be found in some implementations of snapshot isolation, unfortunately doesn't help either.

Automatically preventing write skew requires true serializable isolation.

Some databases allow you to configure constraint, which are then enforced by the database.

If you can't use a serializable isolation level, the second best option to explicitly lock the rows that the transaction depends on.

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

SELECT * FROM doctors

WHERE on_call = true

AND shift_id = 1234 FOR UPDATE;

UPDATE doctors

SET on_call = false WHERE name = 'Alice' AND shift_id = 1234;

COMMIT;BEGIN TRANSACTION;

SELECT * FROM doctors

WHERE on_call = true

AND shift_id = 1234 FOR UPDATE;

UPDATE doctors

SET on_call = false WHERE name = 'Alice' AND shift_id = 1234;

COMMIT;More examples of write skew

- Meeting room booking system

Can't be 2 bookings for the same meeting room at the same time. Before making reservation we check first.

BEGIN TRANSACTION

-- Check for any existing bookings that overlap with the period of noon-1pm

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM bookings

WHERE room_id = 123 AND

end_time > '2015-01-01 12:00' AND star_time < '2015-01-01 13:00';

-- If the previous query returned zero:

INSERT INTO bookings

(room_id, start_time, end_time, user_id)

VALUES (123, '2015-01-01 12:00', '2015-01-01 13:00', 666);

COMMIT;BEGIN TRANSACTION

-- Check for any existing bookings that overlap with the period of noon-1pm

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM bookings

WHERE room_id = 123 AND

end_time > '2015-01-01 12:00' AND star_time < '2015-01-01 13:00';

-- If the previous query returned zero:

INSERT INTO bookings

(room_id, start_time, end_time, user_id)

VALUES (123, '2015-01-01 12:00', '2015-01-01 13:00', 666);

COMMIT;Unfortunately, snapshot isolation does not prevent another user from concurrently inserting a conflicting meeting. In order to guarantee you won’t get sched‐ uling conflicts, you once again need serializable isolation.

- Multiplayer game

Lock won't help you

- Claiming a username

Unique constraint is a simple solution here

- Preventing double-spending

Phantoms causing write skew

Where a write in one transaction changes the result of a search query in another transaction, is called a phantom.

Snapshot isolation avoids phantoms in read-only queries, but in read-write transactions like the examples we discussed, phantoms can lead to particularly tricky cases of write skew.

Materializing conflicts

If the problem of phantoms is that there is no object to which we can attach the locks, perhaps we can artificially introduce a lock object into the database?

Addition tables

Serilizability

Still some race conditions are not prevented.

Isolation levels are hard to understand and inconsistently implemented in different databases.

Difficult to tell whether application code is safe to run at a particular isolation level.

No good tools to help us detect race conditions.

Serializable isolation is usually regarded as a strongest isolation level.

It guarantees that even though transactions may execute in parallel, the end result is the same as if they had executed one at a time, serially, without any concurrency.

The database prevents all possible race conditions.

But if serializable isolation is so much better than the mess of weak isolation levels, then why isn’t everyone using it? To answer this question, we need to look at the options for implementing serializability, and how they perform.

- Literally executing transactions in a serial order

- Two-phase locking

- Optimistic concurrency control techniques such as serializable snapshot isolation

Actual Serial Execution

The simplest way of avoiding concurrency problems is to remove the concurrency entirely: to execute only one transaction at a time, in serial order, on a single thread.

By doing so, we completely sidestep the problem of detecting and preventing con‐ flicts between transactions: the resulting isolation is by definition serializable.

If multi-threaded concurrency was considered essential for getting good performance during the previous 30 years, what changed to make single-threaded execution possible?

RAM became cheap enough that for many use cases is now feasible to keep the entire active dataset in memory.

Database designers realized that OLTP transactions are typically short and make a small number of reads and writes.

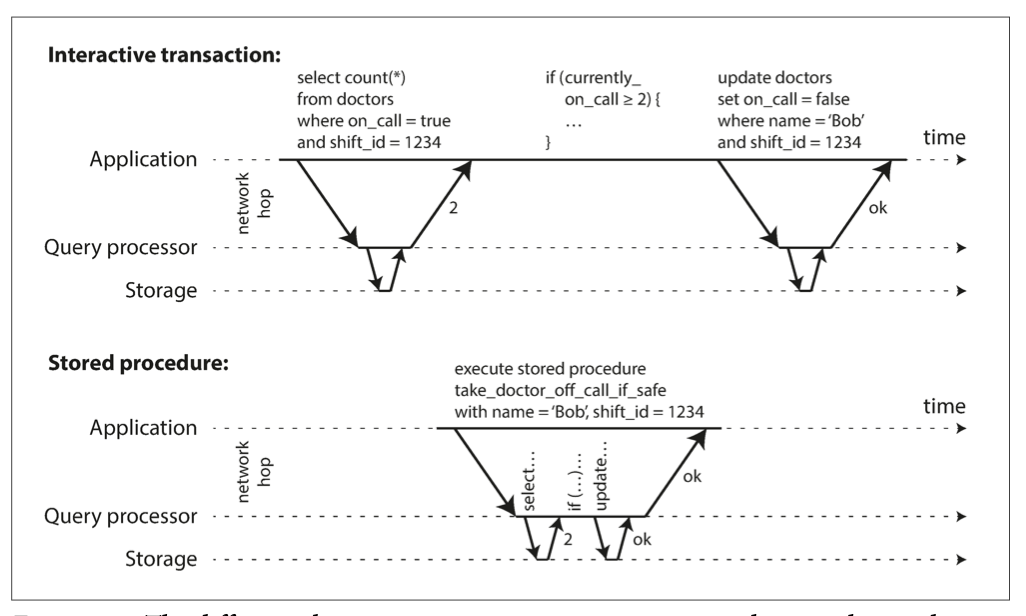

Encapsulating transactions in stored procedures

At the begining designers thought that all user flow must be done with one transaction: searching, input some form data - all in one transaction. But waiting for user input is a long process and it's not good to keep transaction open.

Solution: new HTTP request starts a new transaction.

Even though the human has been taken out of the critical path, transactions have continued to be executed in an interactive client/server style.

App makes a query, reads the result, perhaps makes another query and so on.

In this interactive style of transaction a lot of time is spent in network communication between the application and the database.

If you were to disallow concurrency in the database and only process one transaction at a time, the throughput would be dreadful because the database would spend most of its time waiting for the application.

For this reason, systems with single-threaded serial transaction processing don’t allow interactive multi-statement transactions.

Instead, the app must submit the entire transaction code to the database ahead of time, as a stored procedure.

Pros and cons of stored procedures

Stored procedures have existed for some time in relational databases, and they have been part of the SQL standard, but later they have gained a bad reputation, reasons:

Each database vendor has its own language for stored procedures (PL/pgSQL in PostgreSQL, PL/SQL in Oracle).

Code running in a database is difficult to manage.

A database is often much more performance-sensitive than an app server.

PL/Rust - https://github.com/tcdi/plrust

Modern implementations of stored procedures are using programming languages instead of SQL (e.g Redis Lua scripts).

With stored procedures and in-memory data, executing all transactions on a single thread becomes feasible. As they don’t need to wait for I/O and they avoid the overhead of other concurrency control mechanisms, they can achieve quite good throughput on a single thread.

Partitioning

Single-threaded transaction processor can become a serious bottleneck for application with high write throughput.

In order to scale to multiple CPU cores, and multiple nodes, you can potentially partition yout data.

Each partition can have its own transaction processing thread running independently from the others.

However, for any transaction that needs to access multiple partitions, the database must coordinate the transaction across all the partitions that it touches. The stored procedure needs to be performed in lock-step across all partitions to ensure serializability accross the whole system.

Whether transactions can be single-partition depends very much on the structure of the data used by the application.

Summary of serial execution

- Every transaction must be small and fast.

- It is limited to use cases where the active dataset can fit in memory.

- Write throughput must be low enough to be handled on a single CPU core.

- Cross-partition transactions are possible, but it's not easy to implement.

Two-Phase Locking (2PL)

Locks are often used to prevent dirty writes. If two transacions concurrently try to write to the same object, the lock encures that the second writer must wait until the first one has finished its transaction before it may continue.

2PL is simular, but makes requirements much stronger.

Several transactions are allowed to concurrently read the same object as long as nobody is writing to it.

In 2PL, writerts don't just block writers, they also block readers and vice versa.

In snapshot isolation, readers don't block writers and writers don't block readers.

Implementation of two-phase locking

The blocking of readers and writers is implemented by a having a lock on each object in the database. The lock can be in shared mode or in exclusive mode.

- If want to read, must first acquire the lock in shared mode.

Several transactions allowed to hold the lock in shared mode, but if another transation have exclusive lock, these transactions must wait.

- If want to write, must first acquire the lock in exclusive mode.

Transactions may hold the lock, must wait until any lock exists.

If transaction first read and then writes, must upgrade shared to exclusive.

After a transaction has acquired the lock, must continue hold the lock until commit/abort of transaction.

Deadlocks may happen, database automatically detect them.

Performance of two-phase locking

Transaction throughput and response times of queries are significantly worse under two-phase locking than under weak isolation.

Traditional relational databases don’t limit the duration of a transaction, because they are designed for interactive applications that wait for human input.

Although deadlocks can happen with the lock-based read committed isolation level, they occur much more frequently under 2PL serializable isolation.

Predicate locks

Predicate lock works the same as a shared/exclusive lock, but belongs not to a particular object, it belongs to all objects that match some search condition.

Restricts access as follows:

- If wants to read objects match some condition, it must acquire a shared-mode lock on the conditions of the query.

If another have lock, must wait.

- If wants to insert/update/delete, must check for any predicate lock.

If another have lock, must wait.

The key idea here is that a predicate lock applies even to objects that do not yet exist in the database, but which might be added in the future (phantoms).

If two-phase locking includes predicate locks, the database prevents all forms of write skew and other race conditions, and so its isolation becomes serializable.

Index-range locks

Unfortunately, predicate locks do not perform well: if there are many locks by active transactions, checking for matching locks becomes time-consuming.

For that reason, most databases with 2PL actually implement index-range locking.

It's safe to simplify a predicate by making it match greater set of objects.

Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI)

On the one hand, we have implementations of serializability that don’t perform well (2PL) or don't scale well (serial execution).

On the other hand, we have weak isolation levels that have good performance, but are prone to various race conditions.

An algorithm called serializable snapshot isolation (SSI) is very promising. It provides full serializability, but only a small performance penalty compared to snapshot isolation.

Pessimistic versus optimistic concurrency control

2PL is a so-called pessimistic concurrency control mechanism: it's based on principle that if anything might possible go wrong, it's better to wait until the situation is safe again before doing anything. Like mutual exclusion in multi-threaded programming.

Serial execution is, in a sense, pessimistic: it's equivalent to each transaction having an exclusive lock on entire database (or partition). Compensation - transactions are fast enough.

SSI is an optimistic concurrency control technique. When transaction wants to commit, the database checks whether anything bad happened; if so, the transaction is aborted and has to be retried. Only transactions that executed serializably are allowed to commit.

- High contention (many transactions trying to access the same objects = many aborts)

- Additional transaction load can make performance worse if system is already close to its max

Contention can be reduced with commutative atomic operations, for example increment of counter don't change final state in different execution orders.

Decisions based on an outdated premise

Previously: write skew in snapshot isolation.

Put another way, transaction is taking an action based on premise (a fact that was true at the beginning of the transaction), later when transaction wants to commit, it checks whether premise is still true.

How does the database know if a query result might have changed?

- detecting reads of a stale MVCC object version (uncommitted write occurred before read)

- detecting writes that affects prior reads (the write occurs after the read)

Detecting stale MVCC reads

Recall that SSI isolation is usually implemented by MVCC (multi-version concurrency control).

When a transaction reads from a consistent snapshot in an MVCC database, it ignores writes that were made by any other transactions that hadn't yet committed at the time when the snapshot was taken.

In order to prevent this anomaly, the database needs to trach when a transaction ignores another transaction's writes due to MVCC visibility rules.

When database wants to commit, it checks whether any of the ignored writes have now been committed, and if so, the transaction is aborted.

Detecting writes that affect prior reads

The second case to consider is when another transaction modifies data after it has been read.

In the context of 2PL we discussed index-range locks, which allows to lock access to all rows matching some search query. We can use a simular technique here, except that SSI don't block other transacions.

Each transaction keeps track of which objects it has read, and which objects it has written. When a transaction wants to commit, the database checks whether any other transaction has written to an object that was previously read by the committing transaction.

Performance of serializable snapshot isolation

Less detailed tracking is faster, but may lead to more transactions being aborted than strictly necessary.

In some cases, it's okey for a transaction to read information that was overwritten by another transaction.

Compared to 2PL, the big advantage of SSI is that one transaction doesn't need to block waiting for locks held by another transaction.

Compared to serial execution, serializable snapshot isolation is not limited to the throughput of a single CPU core.

The rate of aborts significantly affects the overall performance of SSI.

Summary

Transactions are an abstraction layer that allows an application to pretend that certain concurrency problems and certain kinds of hardware and software faults don't exist.

Several isolation levels: read commited, snapshot isolation (repeatable read), serializable.

- dirty reads - reading uncommitted data

- dirty writes - overwriting uncommitted data

- read skew (nonrepeatable reads) - different parts of the database at different points in time.

- lost updates - two transactions concurrently reading and writing the same object, one overwriting the other's changes.

- write skew - transaction reads something, makes a decision based on the value it saw, and writes the decision to the database, but by the time it commits, that decision is no longer valid.

- phantom reads - transaction reads objects matching some search condition, another transaction makes a write that affects the results of that search.

Weak isolation levels protect against some of the anomalies, but some also can be solved on application level using explicit locking. Only serializable isolation level protects against all anomalies.

Three different approaches to implementing serializable isolation:

Execution of transactions in a serial order - effective for small transactions, with low throughput requirements.

Two-phase locking (2PL) - standard way of implementing serializably, but have significant performance penalty.

Serializable snapshot isolation (SSI) - optimistic concurrency control mechanism, allowing transaction to proceed without blocking. When a transaction wants to commit, it's checked, and it's aborted if the execution wasnt't serializable.